Role of a Mentor: How to Give Advice

A common question we get asked in our masterclasses is “How do I provide insight without direction? I want to help. I know they’re coming to me for advice. But I don’t want to tell them what to do?”

And quite right too.

This Huffington Post article says it well. “While mentors can offer valuable advice, they should not provide absolute answers. It is the job of the mentor to use a more Socratic method to stimulate critical thought.”

So how do you do this?

Three Guiding Principles for the Role of a Mentor

I recommend three guiding principles when it comes to stimulating thought and generating ideas.

1 Generate as many insights and ideas as possible

The first is to generate as many ideas as possible without judgement or evaluation. When it comes to solving a problem, or making progress in a career there are many more options than are immediately obvious. Some of the options may seem unachievable or unappealing but include them anyway. I think of it like creating a whole smorgasbord of ideas and opportunities.

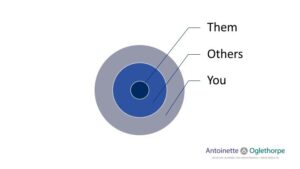

It helps to explore ideas and experiences from a range of sources. One useful framework is the Know-How target.

At the centre is the employee reflecting on their own knowledge and experience. Questions like:

“What was the best you ever did (at this thing?). What went well then?”

“When have you made great progress in your career before? What did you do that helped? What else?”

“When you’ve made career decisions before, what helped you reach the right answer?”

The second level is the knowledge and experience of others. Questions like “Who else do you know who’s made this career move? What strategies did they use?”

And the third level is the knowledge and experience of you as the mentor. You have useful experience and wisdom to offer and employees want to hear it. But, I urge you to take care in how and when you do it as explained below.

2 Start with insights from the employee first

If employees are going to take ownership for their career development, they need to take action on the insights. They are much more likely to do that if they came up with them in the first place.

So, it’s better to explore the employees own thoughts, experience and know-how first. If you don’t do this, in the context of what he or she wants, they may well greet your ideas with a response like “I’ve tried that. It didn’t work.” or “That wouldn’t work.” Or “I haven’t got time for that.”

Think about it. Have you ever tried to lose weight? Like most people, I have – many times! Now there is no shortage of insights into how to lose weight. Ask 100 different people and you’ll hear 100 different experiences. Insights range from low carb eating to slimming clubs to fasting and running marathons. And every single idea and option is a possibility. But there are only a handful of them that I would consider trying.

Let’s say I go to my mentor to talk things through and he starts sharing his experience of losing four stone through meal replacements. I’m likely to do one of two things. I’m either going to sign up for meal replacements thinking “I’d better try this because my mentor says this is the answer.” Or I’m going to stop listening thinking “it’s all right for him but that would never work for me.” Either way, I won’t be energised and empowered to take action and lose weight.

Imagine a different scenario. This time when I go to my mentor, he says “I’m happy to share my experience of losing four stone. But before we do that let’s discuss the thoughts you’ve had. You mentioned you’ve lost weight in the past, what helped then?”

I would then rattle off insights from my own experience. If you’re interested they include calorie counting, running, wedding (goal) and divorce (stress). Other things that helped were low-carb, giving up alcohol, giving up chocolate.

My mentor listens and asks questions to explore the different experiences. Then he goes on to ask “What about friends and family? Do you know anyone else that’s lost weight?” And then I’m generating a whole new set of ideas based on what I know of others (slimming clubs, 5:2, Atkins etc.)

Finally, my mentor says “I did something different. Let me share my experience.” And he tells me about how he lost four stone using meal replacements supported by counselling.

And that brings me to my third principle:

3 Share your own insights in such a way as they can be rejected

When someone has chosen to talk to you about their career or sees you as a mentor, they have awarded you a degree of authority and respect. They are likely to see your insights as “expert advice” even if you don’t intend them that way. To avoid that, you need to make sure they can reject them if they don’t suit them.

Here are some ideas on how to do that:

Ask permission. For example, “would you like a suggestion?” Its unlikely they’ll say “No” but at least you’ve shown that it is a suggestion not direction

Use a caveat. When telling a story from your own experience, a useful preface is “This may not work for you but what I did was…..”

Offer ideas from a third party. You might say, “I knew someone who always tackled this kind of thing like this ….” This has the advantage that the employee is likely to reject ideas more easily if the third party isn’t in the room

Offer ideas from a remote source. An example is, “John Lees has written many articles on this kind of thing and his suggestion would probably be …” This gives the idea expert credibility and yet they can still reject if it doesn’t fit.

I’ve used the example of weight loss in this post because it’s fairly universal but the same principles apply to career challenges and business problems.

What do you think?